For many participants, the program that provides health care to millions of low-income Americans isn’t free. It’s a loan. And the government expects to be repaid.

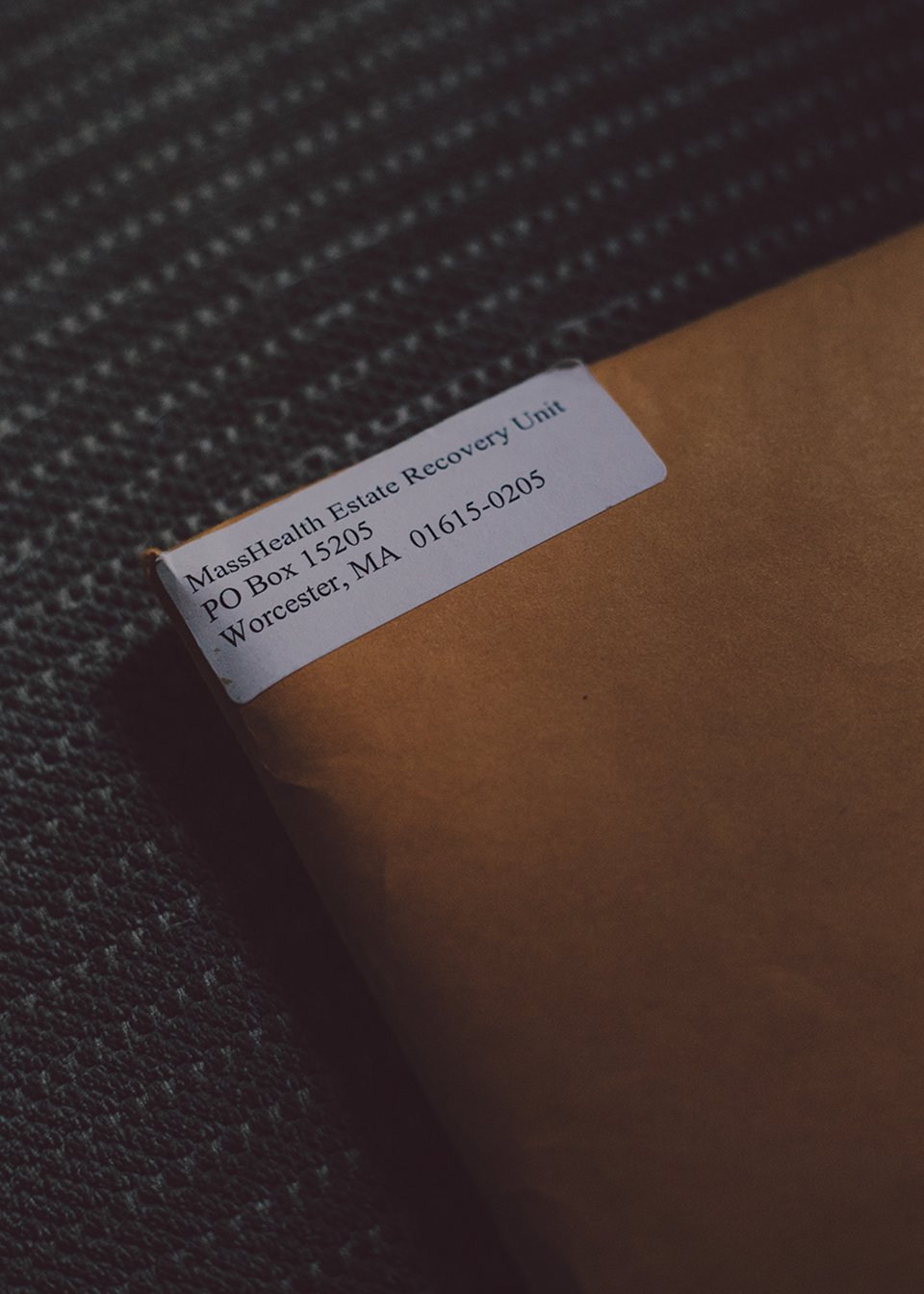

Images above: Tawanda Rhodes believed she would inherit the home her parents had bought in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood in 1979. Then she received a letter from her state’s Medicaid program.

The folded American flag from her father’s military funeral is displayed on the mantel in Tawanda Rhodes’s living room. Joseph Victorian, a descendant of Creole slaves, had enlisted in the Army 10 days after learning that the United States was going to war with Korea.

To hear more feature stories, see our full listor get the Audm iPhone app.

After he was wounded in combat, Joseph was stationed at a military base in Massachusetts. There he met and fell in love with Edna Smith-Rhodes, a young woman who had recently moved to Boston from North Carolina. The couple started a family and eventually settled in the brick towers of the Columbia Point housing project. Joseph took a welding job at a shipyard and pressed laundry on the side; later, Edna would put her southern cooking skills to use in a school cafeteria. In 1979, Joseph and Edna bought a house in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood for $24,000.

Just a few years after they moved in, Joseph died of blood-circulation problems. But by leaving that house to his wife and children, its mortgage satisfied by his life-insurance payout, he died believing that he had secured a legacy for his family, which, in just a few generations, had lifted itself out of slavery, segregation, and poverty to own a piece of the American dream.

When I visited Dorchester this spring, Tawanda, 62, was waiting for me on the front porch of the three-story, vinyl-sided house. She now lives there alone, and on borrowed time.

The trouble began when her mother started showing signs of Alzheimer’s disease. For a while, one of Tawanda’s brothers cared for Edna, but he was sick himself and died in 2004. A guardian of the state admitted Edna into a nursing home and signed her up for the state’s Medicaid program, MassHealth. Tawanda was relieved that her mother was being cared for while she was busy arranging her brother’s funeral. But when she arrived in Boston from Brooklyn, where she and her husband had settled, she heard rumors about MassHealth “robbing people of their homes” as reimbursement for their medical bills.

She soon learned that the rumors held some truth. Medicaid, the government program that provides health care to more than 75 million low-income and disabled Americans, isn’t necessarily free. It’s the only major welfare program that can function like a loan. Medicaid recipients over the age of 55 are expected to repay the government for many medical expenses—and states will seize houses and other assets after those recipients die in order to satisfy the debt.

Sure enough, just weeks after Edna entered the nursing home, Tawanda received a notice that MassHealth had put a lien on the house. Tawanda called the agency and said she wanted to take her mother off Medicaid; she knew Edna had alternatives as a longtime employee of Boston Public Schools. A representative for MassHealth told her not to worry: If she took her mother out of the nursing home, the agency would remove the lien and her mother could continue to receive Medicaid benefits.

Tawanda and her husband, Oliver, decided to move to Boston. They took Edna out of the nursing facility and brought her home to care for her full time. “The place was pretty dilapidated, but I knew it was ours, so my husband and I started bringing it back to life,” Tawanda said.

Oliver and Tawanda had lived a modest but comfortable life in Brooklyn. He worked maintenance for Time Warner; she was a bartender. To renovate the old house, they cashed in all of their savings bonds, about $100,000 worth. They tore up the shag carpeting, refinished the floors, painted the walls, remounted the cabinets. They replaced the 1970s appliances—brown dishwasher, blue toilet, and mustard-colored refrigerator—with modern ones. They paid off Edna’s second mortgage, and her third.

Then, in 2007, Oliver started showing signs of dementia, and shortly thereafter, he too was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Now Tawanda spent her days caring for both her mother and her husband, shuttling them back and forth to doctor’s appointments, giving baths, clipping toenails, changing diapers. She cooked them special dinners “as they started not being able to chew this or swallow that.” After putting them to bed at night, if she wasn’t too tired, she’d mix herself an apple martini and read in the kitchen, often her only hour of relaxation in the day.

This went on until the end of 2009, when Edna died, at home, in Oliver’s arms. Afterward, Tawanda received a letter from the Massachusetts Office of Health and Human Services, which oversees MassHealth, notifying her that the state was seeking “reimbursement from [Edna’s] estate for Medicaid payments made on her behalf.” For Edna’s five years on MassHealth, she owed $198,660.26.

“You must be kidding me,” Tawanda recalled telling the MassHealth caseworker on the phone. As proof, the agency sent her a 28-page itemized bill for “every Band-Aid, every can of Ensure” her mother had used. The state gave Tawanda six months to pay the debt in full, after which she would begin accruing interest at a rate of 12 percent. If she couldn’t afford it, the state could force her to sell the Dorchester house and take its share of the proceeds to settle the debt.

Tawanda’s hair started falling out soon after. She and Oliver, who was in the final stages of Alzheimer’s, had no savings and no jobs. “I said to myself, I don’t care what they do to me. I can take care of myself,” she told me. “But I couldn’t have my dying husband thrown out into the street.”

She wrote to nearly every elected official in the state. “No one would help me,” she said.

Now instead of reading a late-night romance novel, she stayed up researching Medicaid regulations. She discovered that MassHealth allows some exceptions. It will not seize a home occupied by a spouse or a dependent child of the late Medicaid recipient until they die or move. It also offers waivers for financial hardship and an “adult child caregiver” exemption for those who lived with a parent for at least two years and “provided care that allowed the applicant to remain at home.”

That was her, Tawanda thought. She and Oliver had a combined monthly income of just $1,400, well below the threshold to claim financial hardship, and she had taken care of her mother at home for more than five years. But Tawanda told me the state rejected her requests for both exceptions. To qualify for the caregiver exemption, an adult child must live in the house for two years before a parent enters a long-term-care facility. Tawanda doesn’t know why she didn’t qualify for the financial-hardship waiver. “Somebody makes that decision somewhere and that’s it,” says Joanna Allison, the executive director of the Volunteer Lawyers Project, who helped Tawanda find a pro bono lawyer. It didn’t matter that Tawanda had taken her mother out of a nursing home to provide care that saved the Medicaid system hundreds of thousands of dollars, Allison told me.

MassHealth representatives declined to be interviewed for this story and do not comment on individual cases for privacy reasons. A spokesperson said in a statement, “MassHealth’s application and member notification materials provide notices related to estate recovery to ensure applicants are informed of this requirement upfront.”

Tawanda reminded her caseworker of the lien release the agency had sent her years ago. But “what they didn’t tell me then was that they had the right to reinstate” the claim on the property after her mother’s death. This was estate recovery now, the caseworker told her, and there was nothing she could do about it.

Bill Clinton signed the Medicaid Estate Recovery Program into law as part of his deficit-reduction act in 1993. Previously, states had the right to seek repayment for Medicaid debts; the new law made it mandatory. The policy arrived at a time when political rhetoric about individual responsibility dominated the national discourse. The idea that welfare created a “spider’s web of dependency,” as Ronald Reagan once put it, played into fears that taxpayers were shouldering the burden for rampant abuse of the system. Politicians such as then–House Speaker Newt Gingrich tried to justify deep cuts to Medicaid and Medicare by promoting the idea that the programs were exploited by con artists and layabouts—people who “want to be 70 pounds overweight, drink a quart of hard liquor a day, pay no attention to exercise, and then tell you it’s your obligation to make me healthy,” Gingrich said at the time. “You cannot have totally irresponsible humans enjoying the benefits of responsibility.”

Estate recovery was billed as a sensible reform: States would recoup costs for the largest category of Medicaid spending—long-term care, such as nursing homes—from the people most likely to incur them (those 55 and older) in order to replenish the program’s coffers and help others in need. (If there was no money to be had in an estate, then the debt simply went unpaid.) The goal was not to deter people from going on Medicaid, but to mitigate the cost of an already expensive program that the Baby Boomer generation was projected to bankrupt.

Some states initially resisted implementing estate recovery. West Virginia legislators called it “abhorrent” in a federal lawsuit seeking to have it declared unconstitutional. (An appeals court rejected the suit in 2002.) Michigan became the last state to enact recoveries, in 2007, after the federal government threatened to cut its Medicaid funding if it didn’t. Other states opted to collect only high-value assets, or offered exemptions for family farms or estates worth less than a few thousand dollars.

The majority of states, however, took a harder line. Some started allowing pre-death liens, tacking interest onto past-due debts, or limiting the number of hardship waivers granted. The law gave states the option to expand their recovery efforts to include other medical expenses, and many did, collecting for every doctor’s visit, pharmaceutical drug, and surgery that Medicaid covered.

As projected, aging Boomers were straining the system. States’ spending on Medicaid services soared from $137 billion in 1994 to $577 billion in 2017, when the oldest Boomers reached their 70s. Much of the cost comes from long-term care: Medicaid pays for about 50 percent of the nation’s 1.4 million nursing-home residents, coverage that’s often denied by private insurers and even by Medicare, the low-cost federal insurance available to anyone age 65 or over, regardless of income. Medicaid also bears the brunt of costs for patients with illnesses such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, whose needs often fall under “custodial” rather than “medical” care, and who therefore are largely denied coverage by Medicare as well. “It’s Medicaid, a low-income program, that has by default turned into our long-term-care system, and that is absolutely unsustainable,” Matt Salo, the executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors, told me.

Defenders of estate recovery see it both as a way to control the high costs of long-term care and as a necessary check on those who could pay for such care but would rather the government foot the bill. (Nursing homes cost $89,000 a year, on average, for a semiprivate room.) Medicaid, Salo told me, is already struggling to meet the needs of the poorest Americans. Should it also cover long-term care for “someone who’s going to pass hundreds and hundreds of thousands of dollars of assets on to their family?”

But the overwhelming majority of estates are not worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. In 2005, the Public Policy Institute of the AARP published a study of the first decade of mandatory estate recovery. Massachusetts, it found, recovered an average of $16,442 per estate in 2003, in total offsetting a little more than 1 percent of its long-term-care costs that year. That made its efforts among the most effective in the nation. In Kentucky, by contrast, the average amount collected from an estate was $93; the state recovered just 0.25 percent of its long-term-care costs. The total amount states recouped jumped from $72 million in 1996 to $347 million seven years later—but even so, estate recoveries accounted for less than 1 percent of Medicaid’s total nursing-home costs in 2003.

Opponents of estate recovery say that the harm of destabilizing low-income families does not justify the meager returns. “It’s a drop in the bucket given the amount of misery they cause people,” says Patricia McGinnis, the executive director of the California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform, which co-sponsored successful 2016 legislation to limit the assets Medicaid can recover in California. “It’s a terrible program, it’s a punitive program, and it doesn’t do anything to reimburse the billions of dollars spent,” she told me. “The purpose of recovery was to support Medicaid and bring money back, but how? By collecting anything from the poorest of the poor? It’s ridiculous.” By contrast, she says, “you could have a $100,000 heart operation on Medicare and there’s no recovery.” One lawyer in Tennessee recalled a case in which a woman went to her late mother’s Medicaid auction to buy back quilts that had been passed down for generations.

Treva Bollman, an accountant in Elwood, Kansas, had been receiving Medicaid benefits for four years, and was just one year shy of qualifying for Medicare, when she died from cancer. A few months later, her husband, Walter, received a letter from Kansas’s Medicaid Estate Recovery Unit. “I don’t know what this means,” he told his stepdaughter Janie at the time. “It says I owe the state of Kansas a half million dollars or they’re going to take my home.”

Walter lives on a two-acre plot passed down from his great-grandparents. After their town was devastated by a flood in 1993, he and Treva built a double-wide trailer on that ancestral land. Walter, who worked most of his life cutting scrap metal despite a childhood accident that left him with only one arm, has never been on Medicaid. But under Kansas law, the state can collect his house and land, worth an estimated $40,000, to put toward his wife’s debt.

The state will let Walter live the rest of his life there, but that does little to comfort him. “It’s for you kids,” he told Janie.

“If you spend your whole life working for something, you take pride in being able to pass something on to your children,” Janie told me. “They took that sense of pride away from him.”

One of the reasons estate recovery works at all is that few people know about it. Although states disclose the policy in their Medicaid-enrollment forms, it’s often buried in fine print that can easily be overlooked, especially when applicants are anxiously seeking urgent medical care. MassHealth, for example, places its notice about three-quarters of the way down page 20 of its 34-page application: “To the extent permitted by law, and unless exceptions apply, for any eligible person age 55 or older, or any eligible person for whom MassHealth helps pay for care in a nursing home, MassHealth will seek money from the eligible person’s estate after death.”

“It’s all technically accurate, but it’s hard for a nonlawyer to know that that means We’re going to send you a bill,” says Gregory Wilcox, an elder-law attorney in California who’s received “lots of calls from people who are dismayed, shocked,” first by the loss of their loved one and then by the secondary blow of losing their inheritance.

One of the few times estate recovery has made headlines was earlier this decade, during the rollout of the Obama administration’s Medicaid expansion. As more Americans considered Medicaid as a health-insurance option, more came across the fine print. At least three states passed legislation to scale back their recovery policies after public outcry.

I initially learned about estate recovery because it’s going to happen to my own family. My mother enrolled in Medicaid at age 55 after being rejected by other insurers for having once had the preexisting condition of cancer. Last year, she called me crying because she’d heard that the state will take our house in rural Iowa when she dies.

At first I didn’t believe her. She had bought the house on contract for $35,000 in 1995 and had long since made the last payment. It was among the most rewarding decisions of her life, but also one of the riskiest. My parents’ divorce had plunged our family into poverty as my mother struggled to raise two children without child support, on two low-wage jobs, as a teacher’s aide in an elementary school and, on weekends, as a clerk at a health-food store.

When the house we were renting was sold to another family, we found ourselves on the brink of homelessness, at the mercy of a new landlord willing to rent to a single mother for cheap. So when she found a little yellow house on a patch of eastern-Iowa farmland for $400 a month, she hung a tapestry to cover the hole in the kitchen ceiling, and we moved in. A few years later the landlord fell behind on his property taxes, and my mother offered to buy the place. She began reinforcing the weather-beaten porch, reshingling the roof, and painting the plywood floors. She planted sunflowers and a vegetable garden, showing us that even after losing everything, it was still possible to build things that last.

That someone could now take that house from us seemed an impossibly cruel twist. After I hung up the phone, I went online to look for evidence that she was mistaken. What I found instead was page after page of attorney ads warning potential Medicaid recipients to hire them immediately in order to save their home before it was too late.

For us, it was already too late. If my mother stays on Medicaid, the state will almost certainly take our house when she dies; if she transfers it to my or my brother’s name, her Medicaid benefits will be suspended. Unable to afford other insurance options, and unable to go without insurance as a cancer survivor, she has no choice but to remain on the government program.

Unlike Tawanda Rhodes, my brother and I don’t live in the house, nor do our futures depend on inheriting it. But in a country that protects the passage of intergenerational wealth for its most privileged sons and daughters, there’s a special indignity to having to fight for a trailer, or $93, or a shack at the edge of an Iowa cornfield that’s of virtually no value to the government but has meant everything to us. As my wealthier peers in New York inherit summer houses, art collections, and trusts—their riches maximized by an ever-eroding estate tax—it compounds the sense of shame my mother feels in failing to leave her children with even a modest leg up, and in knowing that, had she been better informed, she might have prevented it all.

As I learned from reading the lawyers’ ads, it’s possible to protect your assets by putting them into an irrevocable trust or transferring a deed to a family member before you reach retirement age. “These are not loopholes,” says Michael Amoruso, the president of the National Academy of Elder Law Attorneys. “Congress and the states allow people to plan.”

But the people who consult estate planners are typically those who have wealth to plan for in the first place. “I can’t think of a single person who has come to me to avoid estate recovery,” Gregory Wilcox says, “because they’re usually not aware of it.” Instead, those who do find out about it are those who “come to me for estate planning. I tell them, ‘I’ve got good news for you: I can help you avoid probate, and if you avoid that you can also avoid Medicaid estate recovery.’ They’re not even aware of the need to do that.”

Perversely, then, the program punishes neither the affluent nor those with nothing to lose, but working- and middle-class Americans who, despite the odds, have managed to scrape together a little something to pass on to their children.

Homeownership is one of the greatest catalysts of class mobility in America. Home equity provides a lifeline during emergencies and helps ensure that your children won’t slip down the economic ladder. A typical homeowner’s net worth is $231,400—nearly 45 times that of the average renter’s net worth of $5,200, according to a 2016 Federal Reserve survey.

Homeowners also benefit from considerable financial perks, such as mortgage-interest deductions and capital-gains exemptions inscribed into our tax codes. “Wealthy people aren’t on Medicaid, but they’re getting all kinds of other benefits,” says Brian McCabe, a sociologist at Georgetown and the author of No Place Like Home: Wealth, Community, and the Politics of Homeownership. The mortgage-interest deduction alone—a set of housing subsidies that primarily benefits Americans in the top 20 percent of the income distribution—cost the federal government $66 billion in 2017. By comparison, letting every family of a Medicaid recipient keep their property would cost just $500 million, according to 2011 data gathered by the Office of the Inspector General, the most recent available.

But the benefits of homeownership aren’t merely financial. For many people, owning property is a crucial source of security and status, often marking one’s arrival in the middle class. “It’s the stability of being in a place, of knowing no one’s going to take your house away from you,” McCabe says. “You’ve made it, earned your independence through hard work.” This is especially true among those for whom that dream has always been far out of reach, such as low-income and nonwhite Americans. In a 2018 study in the journal Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, McCabe found that Latinos and African Americans were twice as likely as white Americans to consider social status an important reason to buy a home. “When you’ve historically been excluded from this thing that is centrally American, the ability to achieve it is that much more meaningful,” he says.

If homeownership is one of the greatest means of upward mobility, then estate recovery, a program that strips property from the people who stand to benefit from it the most, is an insidious obstacle, perpetuating cycles of poverty and pushing displaced families back into the welfare system.

Lisa Musgrave, a 56-year-old secretary in Nashville, told me she’ll be homeless when the state forecloses on the house she’s been living in for the past eight years to collect on her late mother’s $171,000 Medicaid debt. “If I could afford to pack up and move down the road to another house, that would be fine,” she said. “But I don’t make $80,000 a year,” which is about what it costs to live comfortably in Nashville, where the median price of a home is $320,000. Musgrave, who works for the state’s handgun-permit office, makes $31,000 before taxes. “There’s no way I would even qualify for a loan to get another home,” she said. She looked into public housing, but there are 10,000 people on the wait list and it’s currently closed.

Musgrave paid an attorney $5,000 from her savings to plead a hardship case to the state in the hopes of negotiating down her mother’s bill. She was denied, without explanation. “No, we’re not able to reduce the bill,” she said was the state’s response. “Go live on the street, live in a box under the bridge. We don’t care; we want our money.”

Last year, for the first time in her life, Tawanda Rhodes didn’t vote. When Election Day came she pulled up in front of the polling station and sat there for a minute, then drove off. “It did not make me feel good,” she said. “But I felt like, Vote for what? No one cares about me.”

Today she hears Democratic presidential candidates talking about a public option and Medicare for All, and she wonders if that would render a low-income program such as Medicaid redundant, and estate recovery a thing of the past. But change probably won’t come soon enough for Tawanda. Last year her attorney told her that her best option was to accept a deal from MassHealth that would keep its claim on the house but allow her to remain there as a tenant until her death. (Oliver died in 2018.) But the contract stipulated that if she fell behind on any of her bills or taxes, or didn’t keep up on repairs, she’d have to vacate. “They were setting me up for failure,” she said.

Tawanda refused to sign. She no longer trusted MassHealth, and she objected to the deal on principle. “From slavery years we never got our 40 acres and a mule; we never got reparations,” she said. “My parents madetheir 40 acres and a mule with blood, sweat, and tears, and now they want that too?”

Money was so tight that paying a bill a little late was almost inevitable. A few months ago, the ceiling in an upstairs bedroom cracked and water poured in. She patched the hole as best she could, but the house needs a new roof, and she says no bank will lend her the money for the project because of the Medicaid debt. “They got my hands locked where I can’t get any equity out of the home, so they figure, ‘It’s gonna fall, the roof is gonna blow one day, and she’s gonna have to get the hell out of there.’ ”

Tawanda doesn’t know which will come down on her first, MassHealth or the roof. Any day now, the state could file suit to force her to sell the house, but she’s decided to stay put. “After my husband died I picked up the sword again,” she said. “I will fight them to the death. I will never, ever give up this fight, and I will never sign a paper saying that they own my house.”

This article appears in the October 2019 print edition with the headline “When Medicaid Takes Everything You Own.”